The Hidden Agenda of American Institutions

“Collectivism, administered with characteristic American efficiency”

Norman Dodd (1899–1987) was an investment banker and independent researcher. In 1953 he was asked to serve as Director of Research for the U.S. House Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations, also referred to as the Reece Committee.

Chaired by Rep. B. Carroll Reece (R.) of Tennessee, the Committee was formed during the McCarthy era to investigate “unAmerican activities” — which Dodd defined as “a determination to effect changes in the country by unconstitutional means.” Congress sought to investigate tax-exempt foundations and comparable institutions (including what we call today “non-governmental organizations” and 501(c)(3) non-profit corporations) to ensure that their aims and activities were consistent with their tax-exempt status.

Norman Dodd

In a 1982 interview with American author G. Edward Griffin, Dodd shared facts he uncovered during his investigation that did not appear in the Congressional committee’s final report — nor in any other official records.

Dodd told Griffin that in an “off-the-record” meeting with Horace Rowan Gaither Jr., then President of the Ford Foundation (and co-founder of the RAND Corporation), Gaither revealed the following:

Mr. Dodd, all of us who have a hand in the making of policies, here, have had experience either with the [Office of Strategic Services] during the war, or with European economic administration after the war. We have had experience operating under directives. These directives emanate, and did emanate, from the White House.

Now, we still operate under just such directives…. Mr. Dodd, we are here to operate in response to similar directives, the substance of which is that we shall use our grant-making power [in order] to alter life in the United States, [so] that it can be comfortably merged with the Soviet Union.

Dodd went on to relate the story of Kathryn Casey, an attorney on Dodd’s research team. Dodd described Casey as a “reasonably brilliant lady” who was highly skeptical of the committee’s mission because she believed the endowments “do so much good.”

Casey was assigned to investigate the Carnegie Endowment by reading the handwritten minute books for the Endowment, which was organized in 1908. Casey spent several weeks “spot reading” sections of the minutes covering time periods that Dodd had flagged, and she recorded her findings via Dictaphone.

Dodd relates that during their first meeting, as Kathryn Casey learned, the Carnegie Endowment trustees “raise a specific question, which they discuss throughout the balance of the year, in a very learned fashion. And the question is: Is there any means known [that is] more effective than war — assuming you wish to alter the life of an entire people? And they conclude that no more effective means than war, to that end, is known to humanity. So then, they raise the second question, and discuss it: namely, how do we involve the United States in a war?”

And finally, “they answer that question as follows: we must control the State Department.”

Casey found that after World War I, the minutes of the Carnegie Endowment trustees reflect a shift in their interests to prevent what Dodd calls “a reversion of life in the United States to what it was prior to 1914, when World War I broke out.”

Dodd determined to educate Congress “as to the effect on the country as a whole of the activities of large endowed foundations over the, then, past 40 years. That effect,” Dodd said, “was to orient our educational system away from support of the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence and implemented in the Constitution.” Dodd wanted Congress to understand “the effect of the wealth which constituted the endowments of those foundations that had been in existence over the largest portion of the span of fifty years,” and to hold them accountable for this change.

Dodd explains that the Carnegie Endowment trustees decided they “must control education in the United States.… What we uncovered was the determination of these large foundations, through their trustees, to actually get control over the content of American education.”

Realizing the task of controlling political thought within the U.S. educational system was too big for them alone, the Carnegie Endowment enlisted the assistance of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Guggenheim Foundation. Together they focused on the teaching of American history, and worked to cultivate their own “stable” of American history professors who would support their agenda: “The future of this country belongs to collectivism, administered with characteristic American efficiency.”

Today, the Carnegie Endowment, formally founded in 1910, describes itself as a think tank. The full name of the institution Casey investigated is the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

carnegieendowment.org

The story that emerged from Kathryn Casey’s investigation never reached the Reece Committee.

Dodd said committee hearings, which began in 1954, were quickly terminated after Rep. Wayne Hayes (D.) from Ohio “put on a show in the public hearing room that was an absolute disgrace. He called Carroll Reece publicly every name in the book.”

Dodd said Congressman Hayes smeared Congressman Reece and his research team with the false allegation of antisemitism: “That was a cooked-up idea,” Dodd said. “It wasn’t true at all.”

Dodd said he believes Hayes’ “furor” was spurred by pressure from the White House. “They had to have something in the way of a rationalization of their decision to do everything they could to stop completion of this investigation, given the direction that it was moving,” he said. “That direction would have been exposure of this Carnegie Endowment story, and the Ford Foundation, and the Guggenheim, and the Rockefeller Foundation — all working in harmony toward the control of education in the United States.”

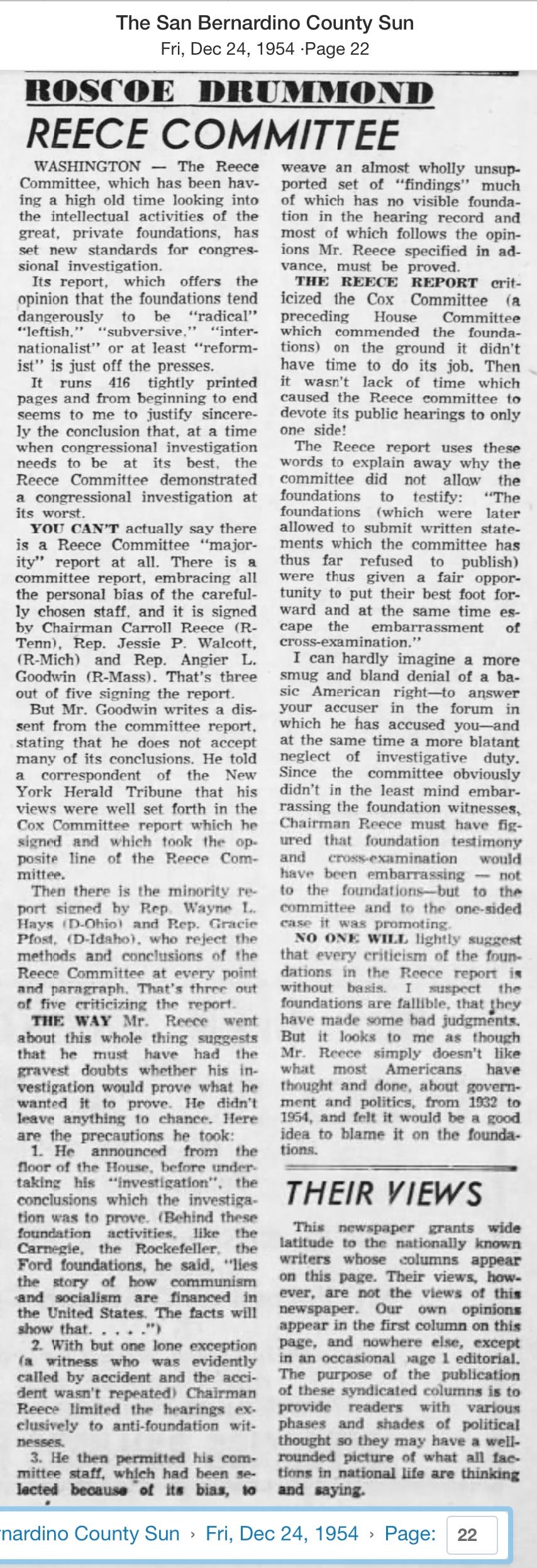

In July 1954 Roscoe Drummond, political journalist and writer of the “Report from Washington” column, wrote1 that the “irresponsible” Reece Committee inquiry had “blown up” in the committees’ face.

The committee has spread onto the public record the most extravagant accusations, with the words “subversion,” “conspiracy,” “plot” and “un-American” being tossed about with abandon, and is slyly shutting up shop without allowing rebuttal from the same rostrum. […]

Chairman Reece had a scheme to try to show that most of the nation’s domestic legislation and most of its foreign policy (from Roosevelt through Eisenhower) was a “plot” and “conspiracy” by a little group of educators and philanthropists, and the sudden dismantling of the public hearings in mid-gutter is ample confession: That these meat-ax charges were not being proved to anybody’s satisfaction and that the public was quickly on to it. […]

In a December 1954 column2 marking the publication of the Reece Committee’s report, Drummond excoriated Congressman Reece for his claim, “announced from the floor of the House, before undertaking his ‘investigation,’” that Reece would prove that behind the foundations’ activities “lies the story of how communism and socialism are financed in the United States.”

Drummond asserted that the committee’s staff was selected “because of their bias” and were permitted to “weave an almost wholly unsupported set of ‘findings’ much of which has no visible foundation in the hearing record.” He slammed the committee for denying the foundations “a basic American right — to answer your accuser in the forum in which he had accused you,” as well as for what he called “blatant neglect of investigative duty.”

Drummond concluded that the committee’s work was terminated early because “Chairman Reece must have figured that foundation testimony and cross-examination would have been embarrassing — not to the foundations, but to the committee and to the one-sided case it was promoting.”

According to Dodd, after the Committee was dissolved Kathryn Casey “was never able to return to her law practice. If it hadn’t been for Carroll Reece’s ability to tuck her away in a job with the Federal Trade Commission, I don’t know what would have happened to Kathryn. Ultimately, she lost her mind as a result of [what she learned]. It was a terrible shock to her. It was a very rough experience, for her, to encounter proof of this kind.”

Drummond, Roscoe. “Reece Committee — Dirt or No Dirt?” Report from Washington by Roscoe Drummond. Valley Times, July 20, 1954. https://www.newspapers.com/image/580289753.

Drummond, Roscoe. “Reece Committee.” San Bernardino County Sun, December 24, 1954. https://www.newspapers.com/image/49262865/