CIS Litigation Forces Transparency of “Humanitarian” Parole Program

Mark Krikorian & Todd Bensman on Parsing Immigration Policy Podcast

Podcast: CIS Litigation Forces Transparency of “Humanitarian” Parole Program. June 27, 2024.

MARK KRIKORIAN: Welcome to Parsing Immigration Policy, the podcast for the Center for Immigration Studies. My name is Mark Krikorian, Executive Director of the Center.

Today we’re going to talk about some information that we extracted from the government at gavel-point, I guess you could say. In other words, through litigation.

And it’s interesting, and it has some important policy implications and consequences. Here to talk about it is Todd Bensman of the Center who has been all over this particular issue, and the Freedom of Information Act request that we filed, and the lawsuit we filed. He’s been all over it, like Inspector Bookman in Seinfeld said, I’ll be all over you like a pit bull on a poodle.

And he’s been all over DHS like a pit bull on a poodle to get this information.

So Todd, thank you for joining us. And before we get into the specific information that we got, this last batch, and why it’s important, in general what was this issue? What is the program, this Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, Venezuelan program, and what information were they not giving out that we had to try to extract from them?

[1:58]

TODD BENSMAN: This is one of two major parole programs, humanitarian parole programs, that the administration I guess invented, out of whole cloth — no one has ever done one of these before — that enables people who would have crossed the southern border illegally, who wanted to or were aspiring to do that, to, instead of adding to all the congestion down there, apply for their illegal entries, like, officially.

To be brought in, in one of two ways. Which is, by land, over the land ports, eight of them to be specific.

And the second parole program was a flights program where you could apply to fly into the United States from a third other country, maybe your own country.

These are not insignificant programs. Between the two of them, probably about a million foreign nationals have been brought into the United States, sight unseen, on something called parole. Which is like a temporary residence. It’s not permanent residence, but it’s like a temporary protected status, for two years, that comes with work authorization. And it’s renewable, supposedly.

[3:22]

KRIKORIAN: Right. Just to be clear, for listeners, you’ve talked about the two parts. The parole program for people just coming to the border, the land border, that’s what uses the CBP One app. And that’s gotten some attention. Where you schedule your illegal immigration at a land port of entry. Across the Rio Grande, or one of the other ones, on the Mexican border.

What we’re talking about, is, the other part, which is, as you said, this direct flights program. Which mainly, almost exclusively, involves Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans. People from those four nationalities. And lets them, as you said, even though they’re not admissible — they don’t have visas — they get an OK to come in for some kind of humanitarian reason. And fly over the border straight into the United States.

[4:16]

BENSMAN: Right. And we think this is legally dubious. There is litigation, a lot of red states are suing over this thing. But it’s working its way, very slowly, through the courts.

In the meantime, something on the order of 460,000 people have been authorized to fly into the United States under this program. It’s a major program, it’s a lot of people.

And we wanted to know where they were flying them into. Because major American cities were complaining, the mayors, staggering under the fiscal burden of all of these immigrants who are showing up, hands out —

[4:49]

KRIKORIAN: Who are showing up in a variety of ways, not just through this program, but every other way they were getting into the country.

BENSMAN: That’s right. But this was one of the ways. But nobody was really talking about it because they weren’t telling us where they were landing. We put in a FOIA [request under the Freedom of Information Act], they didn’t want to tell us where they were landing. We sued, as you know, and we began to, over a long period of time, eke out bits and pieces of information.

We never did really get the specific airport locations, even to this day. But the House Homeland Security Committee got that information — and released it! So, we know 45 cities across the nation, and in what numbers, they were showing up.

Ok, great! Now we know where they’re showing up. But we still wanted to know where they were departing from. The administration was just adamant about not releasing that. They fought tooth and nail over releasing the departure countries.

[6:01]

KRIKORIAN:

And I think the important point here is, the reason they would have done that, is because the public perception — and really any perception — common sense would suggest, well, if it’s Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans, that are being offered this opportunity to come here — the whole program’s illegal, but the point is, it applied to those four nationalities. Everybody would kind of assume, it was sort of unspoken, that, well of course, they were flying from those four countries. Right?

In other words, Haiti is really bad. People were coming from Haiti. Venezuela’s a mess, so they were coming from Venezuela. The very fact that they were so resistant to telling us what countries they came from, I assume, given your both journalistic and intelligence background, you immediately kind of had your spidey sense tingling that there’s got to be something interesting there.

[7:00]

BENSMAN: Yes, that’s exactly right. Because nobody had to guess, really, about why they were doing this program. They sold it to the American public, on the front end, as a humanitarian rescue program.

That people from these nationalities had an urgent humanitarian need to be able to fly into the United States, to get away from terrible situations.

And also, that there was an overriding American public interest in this, which they named in their public documents as “reducing the congestion at the land borders.”

So, we should get them out of their terrible straits, make sure that they don’t have to get on these dangerous trails, maybe get killed along the way. And at the same time, help America by reducing congestion at the border.

So, now, we finally come to a settlement on our lawsuit that includes a provision to release the names of the countries, the departing countries. They give those countries to us.

They won’t tell us how many are leaving from each of these countries, or even rank them in order of volume, or anything like that. Just an alphabetical list.

KRIKORIAN: Right.

[8:20]

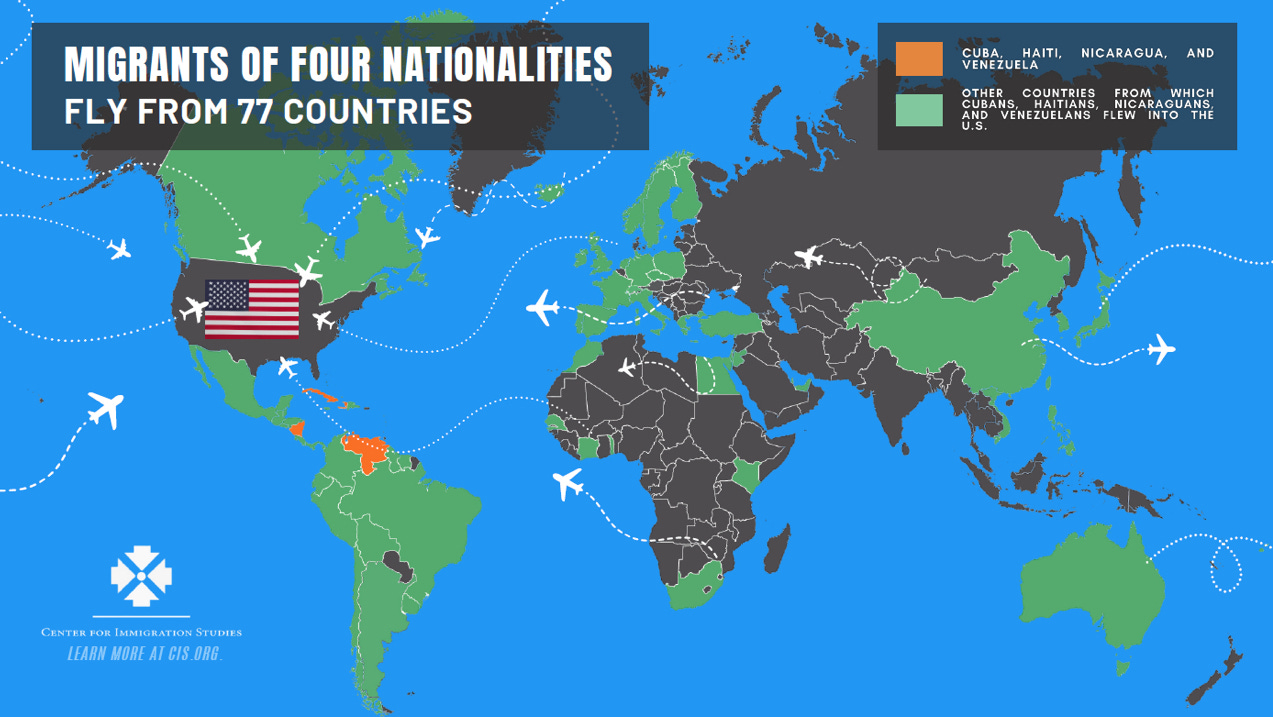

BENSMAN: And it turns out that there were 77 countries. And when you start going through the list, you’re seeing that the vast majority of them are perfectly safe. And nowhere near the migrant trails that they would be forced onto by their terrible straits.

[8:37]

KRIKORIAN: Sure. And just to be clear, it’s the vast majority of countries because they wouldn’t give us numbers.

So, you know, clearly a lot of the Cubans would have come from Cuba. And the Nicaraguans from Nicaragua.

But there’s 73 other countries that they’re coming from, and most of them are not places any of these people were being persecuted.

BENSMAN: Exactly. And to just name some of the countries, France. Germany. Iceland. Fiji, Australia, Canada. These are places that are safe countries, that immigrants all over the world try to bust the borders to get to, and to stay there. Because they’re prosperous, and safe, and orderly.

And they’re certainly nowhere near migrant trails, where something so bad in Iceland was happening that they’d have to go to the Mexican — through Tapachula, or through the Darien Gap or something.

And other countries are also perfectly safe, and far away. Like South Korea. And Taiwan. And even China. Really, strange places that you would never think that Cubans need to get rescued from, or Haitians need to be rescued from.

And I guess the big takeaway of the list, and of having this information, is that the administration is — I’m just gonna say, they were lying about the need for, all the justifications for this program.

They’re just flat out lying about it, in my opinion. They’re certainly being extremely disingenuous about — and I mean in public forums, in speech, in talk, in proposed regulations, all of it — is saying we’re going to give people safe haven from their urgent humanitarian straits.

[10:34]

And it turns out that none of that — or maybe some of it’s true. But nobody’s explaining why we’re rescuing Cubans, Haitians and Venezuelans, you know, from Fiji.

KRIKORIAN: Or Austria, or Switzerland, or — I’m looking at the list of countries — Italy, Finland, Sweden, Brazil, South Korea. Taiwan. It’s ludicrous. The United Arab Emirates, even.

The whole thing is preposterous. And it really does, I mean, what it undermines is this idea that there was an urgent humanitarian need for this program to begin with.

And you also highlighted in the post you did on this, which we’ll have the link in our show notes, that’s on our website, cis dot org, with the list of countries. All kinds of vacation spots!

It wasn’t just Fiji, but, you know, Bahamas, and St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis — all kinds of places where none of these people were being persecuted! There was no urgent humanitarian need for these people to come to the U.S. to claim asylum.

[11:36]

Because that’s kind of the rationale, here, is that’s they’re being let in on this so-called temporary parole — which everybody knows is de facto permanent — in order to apply for asylum and be allowed to stay. Because they’re supposedly fleeing these terrible conditions.

BENSMAN: That’s right. And we’re looking at something like, you know, I mentioned 460,000 and that grows by 30,000 plus a month of those four nationalities. So this thing is ongoing.

Whoever in the White House, or DHS, designed this thing had to have had in mind something else. We can only guess at what that is. I did put in a request for comment, to have somebody come and explain this. I emailed that in, have not heard anything back.

KRIKORIAN: You mean explain the rationale why people from other countries were allowed in?

BENSMAN: Exactly. And I probably, if I could have had somebody in front of me I would have asked, point blank: Can you reconcile your public justifications for this massive program — this huge, hundreds of thousands of people, program — with the reality that you’re flying a great many of them, we don’t know how many, from perfectly safe places.

[12:55]

And, what’s really going on here? Who did this, and why?

We can only speculate.

But I quote Elizabeth Jacobs, here at the Center, who’s quite the expert on this, and comes from USCIS, who I think had the best explanation yet. Which is that this is a hidden immigrant admissions program that they didn’t want to tell anybody about. They just want to just bring in hundreds of thousands of people without having to go through Congress to statutorily declare a new admissions program.

And that’s what this is. And I think the American people, if they’re interested in this, or if they ever want to know what happened, this pretty much puts a lie to everything that the American public has been told, so far, about this flights program.

And I also, now, kind of get why they fought so hard against releasing this information. Because, frankly, if I were them, I’d be a little bit embarrassed about this. You’re busted. You’re just busted.

[14:01]

KRIKORIAN: To reinforce the idea that this was a way to use this supposedly narrow parole power as just a way of goosing more generic immigration, people coming in on this program — and just to be clear, they have to buy their own plane tickets, a lot of people got that wrong. They’re not flown in by the U.S. government.

But people coming in have to have a sponsor in the United States. They have to have somebody requesting that they come here. And so it’s, you know, it’s basically just a way of getting around the limits. Not just the limits on immigration in general, but the waiting lists for family categories.

So, if you’re a relative of someone who’s in the United States, and you’re a Cuban, you might have to wait several years on a waiting list to be able to get in.

This way you can just skip the line, cut the line, and come directly here with this, through what’s supposed to be a narrow emergency program called parole, and bingo you’re in the United States.

[15:07]

And the administration will have de facto increased legal immigration by hundreds of thousands a year. So far this program, what is it, about a year and a half? Has taken in almost half a million people. The administration just increases immigration without, like you said, without getting any approval from Congress.

It’s just one more example of this administration essentially trying to make up immigration law on its own. And frankly, at least so far, getting away with it.

BENSMAN: Right. You know, one of the issues we talked about internally, you and I, and others, is why are all these Cubans in Iceland and all these strange places around the world. And there’s an answer for that. It’s that Cubans and Haitians and Nicaraguans are not just trying to go to the United States. They’re trying to go to any prosperous country where they can live and work, and have a better lifestyle, et cetera.

And we can only guess as to why they would suddenly take advantage of this program as a better option than being in Greece or France or some of these other places.

I guess the best answer is that they may have run into asylums there, or they were having problems legalizing, regularizing into these European countries.

[16:35]

And then all of a sudden the Biden administration throws this big life line. Well, here, you can come to the U.S. All you have to do is get online. And I think probably that’s what happened. A lot of them, maybe they had some family in the U.S. that it was an opportunity to reunify — this is not a family reunification program, by the way.

KRIKORIAN: Yeah, well, but it is. That’s the point. I think that’s probably the main, I would suspect that’s the main explanation. If you’re a Nicaraguan who’s working in Vietnam, one of the countries, here. Or a Venezuelan who managed to get to Norway, but you have relatives in the United States? Well, Norway’s not so bad, you may even have a job.

But if Joe Biden is inviting you to come into the United States, you know, you might take him up on it. Why wouldn’t you?

And then in some other cases, for instance if you were in Vietnam, or the Philippines, or — I’m looking at the list of countries, here — Kenya, or Ivory Coast. You’re safe. You’re not being persecuted — assuming you even were before, which is dubious.

But you can trade up. Because you, yourself, have told stories about migrants you’ve met, south of the border, who were perfectly find where they were. But were trading up because Biden offered them the opportunity to do so.

[18:00]

BENSMAN: Yeah. This is a case of, if you build it, they will come. And they built it, and, they came. The cat’s kind of out of that bag. I do still hope the administration will respond.

I have a lot of questions about this. I think everybody should have a lot of questions about a public policy program as massive as this one. Absolutely huge. As long as it goes on bringing in 30,000 of those four nationalities every single month, into American cities that are struggling under the burdens of taking care of them, and resettling them.

KRIKORIAN: And that’s just this flights program. There’s another, what is it, about […] 35,000 who come in through the land ports using that CBP One program. Not to mention all the people that just walk across the border, turn themselves in, and get let go.

This is a big part, and actually a less reported part of the administration’s attempt at making an end-run around immigration limits.

[19:08]

BENSMAN: Yeah, and I would want to just note one other thing. The last time we reported on this, you know, we took a lot of flack, and there were fact-checkers coming in and talking about: it’s not a secret program, they announced it, so therefore it wasn’t secret, and therefore the whole thing of calling it a secret flights program is wrong. As though the flights program wasn’t happening, because it’s not secret in their view.

But I’m going to have to beg to differ. Because it absolutely was a secret where these people were flying from, that the government fought very hard to maintain. It was a secret that the U.S. airports where they were arriving, and the U.S. cities that were receiving them, that they fought very hard to protect and maintain.

Departure countries and arrival airports are the bread and butter, the meat and potatoes, of the whole thing. So, the whole thing was pretty much secret, other than that it existed.

[20:15]

KRIKORIAN: Yeah. And actually, that’s worth reemphasizing, the reason they gave you. Not for the departure countries, cause, correct me if I’m wrong here, they didn’t actually give us a reason they were withholding the departure countries.

But the reason they wouldn’t tell us what airports people were flying to is because they said, in effect, the program was so onerous that it was creating security vulnerabilities at the airports, and so they didn’t want to tell anybody where the security vulnerabilities were — that they themselves were creating through this illegal program.

BENSMAN: That’s right. And that was a public interest story in its own right, that they were creating vulnerabilities at our airports. I mean, airport security is priority one. Since 9/11. And there they are.

But I have to say, as far as the flights part of this program, there’s not much in the way of secrecy around it any more. And I would just give credit to the Center for the FOIA and for fighting the FOIA all the way to the end. This thing is as viewable and visible to the public now as, maybe, it ever will be.

[21:32]

KRIKORIAN: Only because you and Colin Farnsworth our FOIA director were persistent on this, and ultimately had to go to court to file suit and get this information out of them.

I gotta say, while this last batch of information that we got from them, on the departure countries, is important for this particular story, it does shed light on the broader issue of — who should we be giving asylum to?

Not so much in the issue of, does a particular person qualify, because he’s been persecuted on one of these various grounds? But rather, should people even be allowed to apply for asylum if they were already in a country where they weren’t being persecuted?

And that is a broader issue than just this, but this really does shine a light on it.

For instance, if you’re, let’s say, a Venezuelan. And you are in — I’m looking at the list, here — you’re in Italy, and you’re, I don’t know, working construction, or washing dishes, or something somewhere. Why would you even be permitted to apply for asylum in the United States?

[22:44]

Asylum is supposed to be, essentially, the equivalent of throwing a life preserver to a drowning man. But if you already have a life preserver, even if you want a nicer life preserver — too bad!

Asylum is a limitation on our sovereignty. Where we say, here are our immigration laws, but you get an exception to them. You get to be let in, even though you don’t qualify, because of the fact that you’re being persecuted.

That is a very significant exception we’re making. And it should only be for people who have no other options. And if you’re already living in Sweden, or in Israel, or even in Jordan or Kenya. And you’re from one of these four countries — or from any country other than that one — you already have your asylum.

Sorry! It’s just, under our law, you can still apply, but you shouldn’t be able to. This is a broader discussion we need to have. Why should anybody be permitted to apply for asylum if they came through countries where they weren’t being persecuted?

[24:05]

BENSMAN: Exactly. And you have to assume that most of those who are already in those other countries have actually applied for asylum in them, and maybe even have been granted asylum in them. And yet, here we are, extending humanitarian safe haven to people in those circumstances. It’s an abuse. It’s asylum shopping.

It’s exposed. It’s completely exposed, what they did.

KRIKORIAN: And actually, I think this latest revelation does really underline this whole idea of asylum shopping. Because asylum shopping goes on all the time. We did a panel, I think it was last year, with Trump’s former ambassador to Mexico, Chris Landau, who has been on this program.

And the topic of Remain in Mexico came up. I don’t want to get too far off-topic, here. But Remain in Mexico, if listeners remember, was a program where an illegal immigrant sneaks into the U.S., says he wants asylum, we would say, look, yeah, you get to apply, but you have to wait in Mexico for your hearing date.

The point being, we don’t let them go [in the United States] and never see them again.

Chris Landau’s point — and he was there when Remain in Mexico, he helped negotiate it. And he said, look, it was perfectly ok, it was a good idea at the time, but it was a half measure.

The real question is — why would anyone, who wasn’t Mexican, be even allowed to pass through Mexico and then apply for asylum at the U.S. border? Mexico has an asylum system. Mexico, in fact, is the number three country in the world receiving asylum applications, after the U.S. and Germany.

[25:46]

And your latest information shows that some of the Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans covered by this actually flew in from Mexico!

Well, there’s just no excuse for that. Not because it’s illegal — it, unfortunately, is legal. But there’s no excuse for the law permitting such a thing to happen. And this administration’s, really, abuse of parole through this flights program, I think, really should focus people’s attention on the idea of asylum shopping, and how outrageous it is.

BENSMAN: Right. And my understanding of the asylum law, as it stands, is that there’s nothing in it that specifically prohibits people who have asylum elsewhere from then claiming it in the United States — except for Canada, which, there’s a specific agreement.

KRIKORIAN: Right.

[26:41]

BENSMAN: This really underlines the need for more agreements like that, if not additional amendments, and statutes, that could prohibit this sort of thing from happening.

KRIKORIAN: Yeah, I think statutory change is the way to go. And that’s not going to happen in this administration. But I could see, if there were a new administration in a new Congress, that changing the asylum law would be a real possibility.

And, as much as I’ve said elsewhere, and written, that we really need to withdraw from the UN refugee treaty, in this instance, we wouldn’t have to, to change the law.

Because the UN — it’s called the Convention on the Status of Refugees, and we’ve signed on to the corollary to it called the Protocol — it says that an illegal immigrant can’t be denied asylum just because he’s illegal. But, that only applies if he comes directly from the country where he claims to have been persecuted. And no one passing through Mexico, except Mexicans, can claim that they came directly from the country where they claim to be persecuted.

The people who flew from these 74 other countries, in this particular instance, can’t claim that, either. If you’re a Nicaraguan flying into the U.S. from Portugal, or a Venezuelan going to the U.S. from South Africa, under these direct flights programs, you’re not coming directly from the country where you’re being persecuted.

[28:18]

And so, even though our asylum law does permit you to apply for asylum, the UN treaty does not mandate that. And, so, we need to change that, regardless of whether we pull out of the treaty. That’s a whole other show. But this issue, the information that you uncovered from this direct flights program really does call out for the need to fix our asylum system. Something that was a holdover from the cold war, and the UN rules were written a lifetime ago. And reform of our interpretation of them in our law is long, long overdue.

So, thanks for joining us, Todd, thanks for making time for this. And we will include links to the report that we’ve been talking about, here, and that report itself has links to something like a dozen earlier reports that Todd had done on this issue of the direct flights program.

Where were these people going? What states?

They wouldn’t tell us what airports.

Where are they coming from, what are the numbers, et cetera, that’s all there. And it’s really to Todd’s credit, and to Colin Farnsworth, our director of our FOIA program, for forcing the government to make this information public — something they had absolutely no intention of doing, until we made them.

So, thank you, Todd. […]